A journey from Oeko-Institut to Australia

Planning

All the travel advice was that making the necessary arrangements for taking the trans-sib would take a comfortable six months: we had six weeks. We largely pre-organised all our visas, travel and accommodation to cover the first two weeks of our journey: from Berlin to Hanoi. We obtained our entry visa for Vietnam in the southern Chinese city of Nanning. The pre-scheduling was necessary in order to satisfy entry visa requirements for Russia, Mongolia and China. We booked only as far as Hanoi partly in case of major hiccup – but also because that was all we had time for. We collected our passports with visas on the very morning of our departure.

Leaving Berlin-Kreuzberg

Leaving Berlin-Kreuzberg

Departing

Our friends helped us do the final pack and walked with us from our home in Kreuzberg across the Spree to Ostbahnhof where we boarded the overnight train to Moscow: a very comfortable way to leave after the busy-ness of packing and farewells. I can vividly recall the support and enthusiasm of all my colleagues and housemates for us taking the trans-Siberian. I can still feel it: that excitement carried us all the way to Australia.

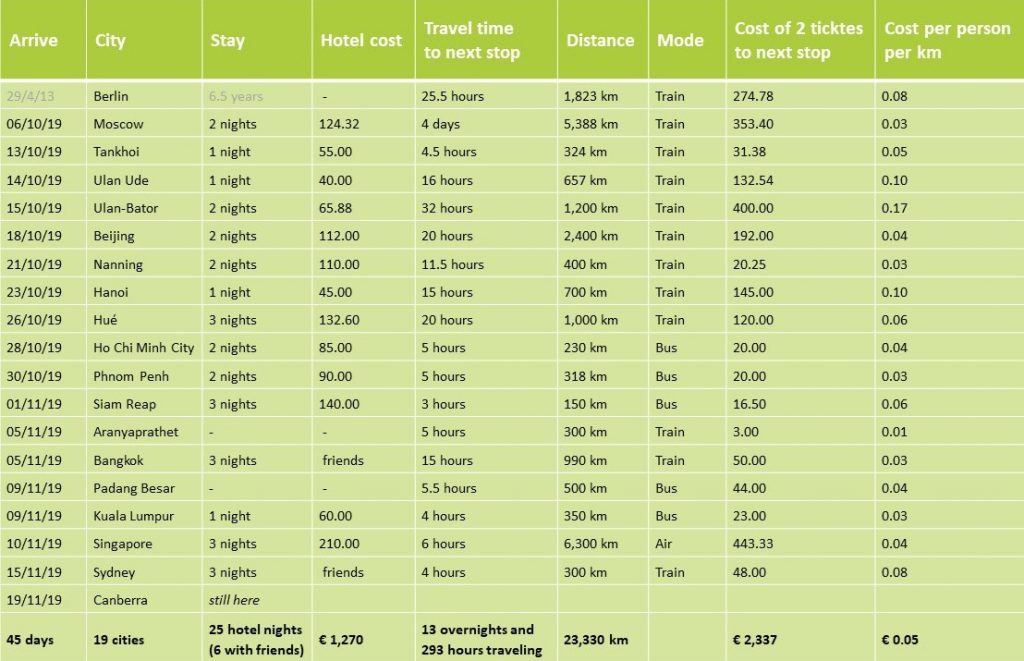

Largely by train and bus

A train journey from Berlin to Canberra was a beautiful way to travel: a really appropriate way to make the change between living in Germany and re-establishing ourselves back in Australia. I found it very hard to make notes along the way or write anything much. In a way our journey to Canberra was like one big movie: and you don’t really stop and take notes in a movie (unless you are a reviewer).

The first three weeks of our journey was all by train: Berlin to Moscow, across Siberia to Lake Baikal and Ulan-Ude, down through Mongolia - Ulaanbaatar and on to Beijing (where the city traffic has been transformed by electric motorcycles and the banishment of petrol motorcycles, bliss); down through China to Nanning and into Vietnam - Hanoi, Huè and Ho Chi Minh City.

Our first buses were across to Phnom Penh and then to Siem Reap where we paused for three days and took a tour of Angkor Wat; and took a bus again to Aranyaprathet on the Cambodian-Thai border. Our first non-aircon trains were from here to Bangkok and subsequently down the Malay peninsula to Padang Besar on the Thai-Malaysian border. The leg to Kuala Lumpur and through to Singapore was also by bus. It was a great trip - a really great trip but not much time for rest. All along this long journey the effects of human proliferation dominated the landscape.

Waste disposal in Hué

Waste disposal in Hué

Travelers along the way

It has certainly been a great way to travel. We loved being on the train. One thing that does stand out was our connection with friends and travellers along the way. Train travel often facilitates those little communities that form, connect and share in each new compartment.

On our overnight train to Moscow we shared our compartment with a Russian grandma. A real babushka who shared with us her passion and craft for making dolls. Outwards from Moscow our first companion was an ex-policeman from the Caucasus. He was rapt to discover that he had google translate on his phone and gave us a fairly detailed biography. He left the police to return to the family baking business. At that time he was travelling two or three hours north-east of the capital to check out and probably buy a used car for his sister.

And thus, our journey continued across Siberia and down through Southeast Asia: connecting, talking, resting, parting or travelling on with French, UK, Singapore, Mongolian, Vietnamese, Thai and Chinese companions: all the way to Singapore: but I'm getting ahead of myself.

Public transport in Signapore: No durian allowed!

Public transport in Signapore: No durian allowed!

The base pattern of our travel was to stay two nights at each major change. We had two nights in Moscow before boarding the Trans-Sib. After packing-up our lives in Berlin we were glad to sit and look at the monotonous and magnificent scenery for a few days.

In most cities we arranged a hotel close by so that we could walk from the station. Where we did negotiate local public transport – often without the internet: we then felt all puffed up and proud of ourselves as if we were the first people in the world to ever figure these things out.

Stop overs

Compared to long distance air travel, the time we spend in our train seats was huge and the stopovers are still relatively brief. The stop overs that we made on the trip while providing some opportunity for rest and sightseeing, felt a lot like international airport transit stops where you have to hurry to rearrange the forward connections.

From Moscow, we stayed on the train for four days until we were at Lake Baikal. We really enjoyed the four days of rest and didn’t find it difficult at all. Indeed, there were some subsequent train journeys - like when we went through Vietnam, that were far more challenging. We crossed the Urals at night, so I missed my personal exit from Europe. After four days and four nights we were happy to get off the train at the small village of Tanhoi on the shores of Lake Baikal.

One day in the region of Lake Baikal is not nearly enough - but if we stopped in all the places where we wanted to explore, then the journey would have lasted for ever: which it does - I’m so pleased that I stopped in Berlin for six years.

Internet connectivity in China is very controlled and constrained, and travelling across Siberia and Mongolia was stupendous. But who wants to wrestle with a device rather than take it all in. Yes, just like everyone says, in China the internet = the internot: a banal reality but still quite a shock.

Arriving in Hanoi at 5am, the surprise was finding out that the train journey ended at Gia Lam Station in north suburbs of Hanoi. We would of course have checked this before arriving but for the internet in China.

Washed-up in Bangkok

The major hiccup in Bangkok was that one of our passports found its way into a washing machine, which meant that we couldn’t continue our journey through Indonesia as actually planned. We dashed to the Aussie embassy three days running and got an ‘emergency passport’: yay! This was fine for entering Malaysia and Singapore. But not so for Indonesia. The Indonesian embassy in Singapore made it quite clear that entry on emergency passports requires a visa for entry and that the application process with such a passport would require lots of documentation and would take at least seven working days to process.

One clean passport

One clean passport

So we took a couple of days to reach equilibrium on this - poor rich people missing out. Singapore was the most expensive city on our travels. Even though dining out in Singapore was the best we didn’t want to stay for ten days. We missed our archipelago leg: boohoo - but we had not established exactly how we should make our way from Bali to Sydney. We took a plane from Singapore to Sydney (only six hours, so easy), and completed our journey by taking the train from Sydney to Canberra: a fitting final leg.

Draft travel times

Draft travel times

Graham Anderson was a scientist at the Öko-Institut until 2019. He worked in the Energy & Climate Protection Division in Berlin until he returned to his home country Australia.